Colombian Mochila: A Deep Dive

Explore the vibrant craftsmanship behind Colombian Mochilas, a cultural icon.

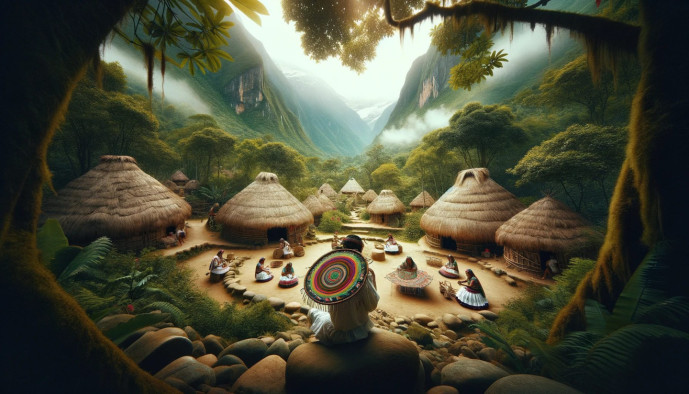

Ever admired the vibrant colors and intricate patterns of a Colombian mochila bag? These aren't just accessories; they're wearable stories, woven with generations of skill and cultural significance. If you've ever wondered, "What exactly is a Colombian mochila and where does its magic come from?", then you've come to the right place.

This deep dive will take you on a journey into the heart of these remarkable creations. We'll explore what makes a mochila uniquely Colombian, honor the indigenous weavers who are the keepers of this sacred tradition, and reveal the artistry and dedication that goes into every single stitch. Prepare to be captivated by the soul of the mochila.

Essentials

What is a Colombian Mochila?

More Than Just a Handbag

At its simplest, a Colombian Mochila is a traditional, handcrafted bag, meticulously woven by the indigenous peoples of Colombia. Yet, to define it merely as a handbag is to overlook its profound significance. Each Mochila is a vessel of identity, a tangible piece of ancestral heritage, and a vibrant symbol of Colombia’s rich cultural tapestry. It is far more than an accessory; it is a narrative woven from thread, carrying the history, cosmology, and spirit of its creators.

The function of the Mochila extends from the purely practical to the deeply sacred. In daily life, it serves to carry everything from food and personal items to the coca leaves essential for spiritual rituals. In a ceremonial context, however, it transforms into a sacred object. For many indigenous communities, the Mochila is a representation of the womb, a symbol of fertility, creation, and the connection between humanity and the earth. It is an inseparable part of traditional attire and a constant companion from birth to death.

A Glimpse into its Ancient Origins

The art of weaving in the lands that are now Colombia is an ancient tradition with roots stretching deep into the pre-Columbian era. Archaeological evidence, including ceramic figures adorned with small bags and textile fragments preserved in the dry mountain climates, points to a sophisticated and long-standing weaving culture. These early communities mastered the use of native fibers like cotton, fique (a type of agave), and wool to create functional and symbolic textiles long before the arrival of Europeans.

Over centuries, the Mochila has evolved, yet its essence remains unchanged. The techniques, patterns, and spiritual beliefs embedded in each bag have been passed down through countless generations, primarily from mother to daughter or, in some communities, from elder to apprentice. While new materials and color palettes have been introduced over time, the fundamental craft endures as a powerful act of cultural preservation. Each stitch is a connection to the past, and each completed bag is a promise for the tradition’s future.

The Indigenous Weavers: Keepers of a Sacred Tradition

A Mochila is never just an object; it is the physical manifestation of a culture’s worldview, history, and spiritual beliefs. Behind every bag is a weaver, a community, and a tradition passed down through countless generations. To understand the Mochila is to meet the people who breathe life into its threads.

The Wayuu and the World-Famous “Mochila Wayuu”

In the arid, sun-drenched landscape of the La Guajira Peninsula, which straddles the border of Colombia and Venezuela, live the Wayuu people. Their contribution to this craft, the Mochila Wayuu, is perhaps the most internationally recognized, celebrated for its dazzling colors and intricate designs. Discover more about this unique region in our Guajira Travel Guide.

Wayuu tradition tells of Walekerü, a mythical spider-woman who taught the very first Wayuu woman how to weave. As she wove, she imparted her wisdom, creating patterns that mirrored the stars, the land, and the creatures around her. This legend underscores the sacred nature of weaving in Wayuu culture. The key characteristics of a Mochila Wayuu are unmistakable:

- Vibrant Colors: A brilliant palette that reflects the vividness of the Caribbean landscape and the expressive nature of the Wayuu people.

- Intricate Geometric Patterns (Kanasü): These are not mere decorations but a complex visual language representing elements of their cosmology, environment, and daily life.

- A Signature Circular Bottom: Every Wayuu bag begins with a perfectly flat, circular base, from which the body of the bag is meticulously built upwards.

For the Wayuu, weaving is a profoundly matriarchal art. A young girl learns to weave from her mother and grandmother, a rite of passage that marks her journey into womanhood. The skill is a source of pride, wisdom, and economic independence for Wayuu women, who are the pillars of their communities.

The Arhuaco and the Spiritual “Tutu Iku”

Deep within the sacred mountains of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the Arhuaco people create a Mochila of a completely different character. Known as the Tutu Iku, their bag is a quiet, contemplative masterpiece that embodies their profound spiritual connection to the earth.

Unlike the vibrant Wayuu bags, the Tutu Iku is crafted from the undyed wool of native sheep. Its earthy tones of cream, brown, and grey are not a stylistic choice but a direct representation of the sacred snow-capped peaks of the Sierra, which the Arhuaco consider the heart of the world. The symbolism is central to its creation; the Tutu Iku is seen as a physical representation of the womb of the universal mother. It is a sacred container for coca leaves, personal items, and, most importantly, for thoughts. The Arhuaco believe their thoughts are woven into the bag, making it a diary of their spiritual state.

In a fascinating contrast to the Wayuu, it is the Arhuaco men who weave their own Tutu Iku. A man begins to weave his first bag as a boy, and the act of creation is a form of meditation and a reflection of his maturity and connection to ancestral knowledge.

Other Weaving Peoples: Kogi, Kankuamo, and Wiwa

While the Wayuu and Arhuaco styles are prominent, it is crucial to understand that “Mochila” is a broad term encompassing a rich diversity of traditions. A true deep dive reveals the unique contributions of other indigenous peoples, particularly from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Learn more about exploring this incredible region in our comprehensive Colombia Travel Guide.

- Kogi Mochilas: The Kogi, who consider themselves the “Elder Brothers” of humanity, often create their mochilas from fique (a fiber from the maguey plant). The natural, off-white color of the fiber is intentional, symbolizing the purity and integrity of their connection to the natural world. Discover more about the spiritual traditions of the Koguis of Colombia.

- Kankuamo Mochilas: The Kankuamo people, also from the Sierra, have a distinctive style easily recognized by its bold, vertical stripe patterns. Their designs carry their own set of meanings and represent a unique cultural identity within the broader Sierra Nevada spiritual framework.

- Wiwa Mochilas: Sharing the same sacred mountain home, the Wiwa also weave mochilas that are integral to their culture. While sharing materials and some philosophical underpinnings with their neighbors, their patterns and specific weaving techniques are distinctly their own, reflecting their particular interpretation of the cosmic order.

Recognizing these distinctions is essential. Each style tells a different story, is born from a different set of hands, and carries a unique piece of Colombia’s ancestral soul. Lumping them all together overlooks the rich cultural tapestry that makes the Colombian Mochila so extraordinary.

The Art of Creation: A Labor of Time and Spirit

A genuine Colombian Mochila is not merely an accessory; it is the culmination of weeks, sometimes months, of patient labor, ancestral knowledge, and spiritual intention. Each bag is a testament to a process that honors the earth, the hands that shape it, and the stories it is destined to carry. To understand a Mochila is to understand the journey from a single fiber to a finished masterpiece.

From Raw Fiber to Spun Thread

The creation begins with the earth itself. The materials are not sourced from a factory but harvested directly from the environment, each chosen for its unique properties and cultural significance.

- Harvesting and Preparing Materials: The primary fibers include native cotton (algodón), which is cleaned and carded by hand; wool (lana) from sheep raised in the high-altitude climates of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta; and fique, a strong, fibrous plant from the agave family, used by communities like the Kogi for its durability.

- The Spinning Process: Once cleaned and prepared, the raw fibers are transformed into thread. This is traditionally done using a simple yet effective tool: the drop spindle. The artisan meticulously twists the fibers, drawing them out to create a continuous, even thread. This is a highly skilled and time-consuming step that dictates the quality and fineness of the final weave.

- Natural Dyes: For the vibrant colors of the Wayuu Mochila, artisans turn to a natural pharmacy of local resources. Dyes are extracted from plants, minerals, and even insects found in the arid La Guajira desert. Tree bark, seeds, flowers, and leaves are boiled for hours to yield a rich palette of reds, yellows, browns, and blues, each color deeply connected to the surrounding landscape.

The Weaving Process: A Meditative Craft

With spools of hand-spun thread ready, the weaver begins the slow, rhythmic process of giving the bag its form. This is a meditative act, where each stitch is a thought and each row a line in a story. The technique is a form of crochet or looping, but its execution is unique to these traditions.

- Techniques: The most renowned Wayuu Mochilas are made using the single-thread (una hebra) technique. This incredibly dense and tight weave creates a detailed, almost pixelated pattern and a bag that is both lightweight and remarkably strong. A more common and faster method is the double-thread (doble hebra) technique, which results in a thicker, heavier bag with slightly less intricate pattern definition.

- The Time Commitment: The dedication required cannot be overstated. A medium-sized, single-thread Wayuu Mochila can take a weaver anywhere from 15 to 25 full days of work to complete. Larger or more complex designs, particularly the spiritual Tutu Iku of the Arhuaco, can take even longer. This profound investment of time is what imbues each bag with its unique spirit.

- The Circular Weaving Method: A hallmark of the Mochila is its seamless construction. The weaver begins with a flat, circular base, which forms the “thought” or origin of the bag. From there, they work upwards in a continuous spiral, meticulously looping the thread to build the cylindrical body of the bag. This method ensures both structural integrity and symbolic completeness.

The Finishing Touches

The creation is not complete once the body of the bag is formed. The final elements are crafted with the same level of care and artistry, ensuring the finished piece is a cohesive work of art.

- The “Gaza”: The Intricately Woven Strap: The strap, or gaza, is a masterpiece in its own right. It is not simply attached but is handwoven, often on a small, vertical loom. The patterns on the gaza are incredibly complex and frequently echo the geometric motifs found on the bag, requiring immense skill and precision to create.

- The Tassels: The distinctive tassels, or borlas, that adorn the drawstring are the final flourish. They are carefully crafted to be full and symmetrical, adding a touch of elegance and movement. Beyond decoration, they are considered an essential part of the bag’s identity, completing the weaver’s creative expression.

Decoding the Symbols: Stories Woven in Thread

A Colombian Mochila is far more than a beautifully crafted accessory; it is a canvas of cultural identity and a repository of ancestral stories. Each stitch and pattern is a word in a silent language, conveying beliefs, myths, and a profound connection to the natural world. To understand a Mochila is to read the story woven into its very fabric.

The Kanasü: The Geometric Language of the Wayuu

The intricate, geometric designs that adorn Wayuu Mochilas are known as Kanasü. This ancient art form is a visual representation of the Wayuu worldview, passed down from mother to daughter for countless generations. Each abstract pattern is derived from the environment and the cosmos, transforming observations of nature into a sophisticated design language. These motifs are not merely decorative; they are symbols of the weaver’s lineage, skill, and understanding of her culture.

Some of the most common motifs include:

- Pulikerüü: Representing the tracks of a mule, this pattern symbolizes journeys and the paths one takes through life.

- Pasalouma: Literally “the cow’s intestines,” this complex, winding pattern reflects the value of livestock and the intricate, interconnected nature of life.

- Kalia: This design mimics the geometric form of a wooden roof beam used in traditional Wayuu homes, symbolizing protection, family, and community.

- Ule’sia: A clean, straight line that represents the clear and righteous path, embodying clarity and simplicity in thought and action.

The Arhuaco Philosophy in Weaving

For the Arhuaco people of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the Mochila, or Tutu Iku, is a deeply personal and spiritual object. The patterns woven into their bags are a direct reflection of their philosophy, which sees the Sierra as the heart of the world. The designs are abstract representations of the sacred landscape—the snow-capped peaks, the winding rivers, the animals that inhabit the mountains, and the cosmic order.

More profoundly, the Arhuaco Mochila is considered a “thought holder.” The process of weaving is a meditative act, and the weaver imbues the bag with his thoughts, intentions, and spiritual energy. The finished Mochila is a physical manifestation of the weaver’s state of being at the time of its creation. It is said that by looking at a man’s Tutu Iku, one can understand his thoughts and his connection to the universal mother. It is a tangible piece of his soul, carried with him throughout his life.

The Mochila in the Modern World

From Indigenous Utility to Global Fashion Icon

In recent decades, the Colombian mochila has journeyed far from the remote mountains and deserts of its origin, finding a new and prominent place on the global stage. Once purely a utilitarian and spiritual object, it has been embraced by international fashion, becoming a staple of the “boho-chic” aesthetic. Its vibrant colors, intricate patterns, and handcrafted authenticity resonated with a desire for unique, story-rich accessories, catapulting it onto catwalks, into high-fashion magazines, and onto the arms of celebrities.

This rise in popularity led to collaborations between indigenous communities and international designers. Some of these partnerships have been models of respectful cooperation, bringing wider recognition and economic benefit to the weavers. However, this global spotlight also casts a long shadow, raising complex questions about cultural appropriation versus genuine appreciation. When a sacred design is decontextualized and mass-marketed without acknowledgment or fair compensation, its spiritual significance is diminished. The challenge lies in celebrating the beauty of the mochila while honoring its deep cultural roots and the artisans who are its rightful custodians.

Economic Empowerment and Ethical Concerns

For many Wayuu, Arhuaco, Kogi, and other indigenous families, the sale of mochilas has become a primary source of income. This economic lifeline provides a means to purchase food, fund education, and sustain their communities in the face of modern economic pressures. The global demand for their craft offers a powerful opportunity for financial independence and the preservation of their cultural heritage. When managed equitably, this exchange can be mutually beneficial, fostering a connection between the consumer and the creator.

However, this opportunity is fraught with ethical peril. The concept of fair trade is paramount. A weaver who spends weeks meticulously crafting a single bag deserves compensation that reflects her time, skill, and the cultural knowledge embedded in her work. Unfortunately, many intermediaries exploit artisans, paying them a fraction of the bag’s final retail price.

Perhaps the greatest threat is the proliferation of mass-produced fakes. Machine-made imitations, often crafted from synthetic materials like acrylic, flood tourist markets and online stores. These counterfeit bags not only devalue the authentic craft but also directly harm the livelihood of the indigenous weavers. As a consumer, your purchasing power is a powerful tool. Choosing an authentic, ethically sourced mochila is not just a transaction; it is an act of cultural respect and economic solidarity. It requires a conscious decision to look beyond the price tag and inquire about the story, the materials, and the people behind the bag you choose to carry.

A Practical Guide for the Conscious Buyer

Acquiring a mochila is more than a simple purchase; it is an act of becoming a custodian for a piece of cultural heritage. To honor the tradition and the artisan, it is essential to approach buying with awareness and intention. This guide will help you discern an authentic, ethically sourced mochila and care for it as the treasure it is.

How to Identify an Authentic, Handcrafted Mochila

The global popularity of the mochila has unfortunately led to a market flooded with mass-produced imitations. An authentic bag, however, reveals its story through its texture, stitches, and subtle imperfections. Training your eye and hand to recognize true craftsmanship is the first step in conscious consumption.

- Stitching: Examine the weave closely. An authentic Wayuu mochila, for instance, is made with a single-thread crochet technique that results in an incredibly tight, dense, and rigid fabric. The stitches should be small and consistent, but with the slight irregularities that signal human hands at work, not the perfect uniformity of a machine.

- Material: Touch is your best tool. Authentic mochilas are crafted from natural fibers like cotton, wool, or the agave-derived fique. These materials have a distinct, slightly coarse, and substantial feel. Synthetic acrylic, common in fakes, often feels slick, light, and may have an unnatural sheen.

- Symmetry and Design: A handcrafted item is a testament to the artisan’s skill, not a machine’s precision. Look for minor variations in the geometric patterns or a slightly imperfect roundness to the base. These are not flaws; they are the signature of authenticity and the soul of the piece.

- The Strap: The strap, or gaza, is a crucial indicator. On a genuine mochila, the strap is a masterpiece in itself, intricately woven by hand with complex patterns that echo the bag’s design. Machine-made straps are typically simpler, flatter, and lack the same density and detail.

Where to Buy Responsibly

Ensuring that your purchase directly benefits the weavers and their communities is paramount. The goal is to participate in a cycle of appreciation, not appropriation, by supporting fair trade practices that empower the artisans who keep this tradition alive.

- Directly from Artisan Cooperatives: When traveling in Colombia, purchasing directly from a community or a reputable local cooperative is the most impactful way to buy. This ensures the maximum amount of money goes to the weaver.

- Certified Fair-Trade Retailers: Look for retailers, both physical and online, that are transparent about their supply chain. Certifications from organizations like the Fair Trade Federation indicate a commitment to ethical sourcing and fair wages.

- Ethical Online Marketplaces: Many online stores now specialize in artisan-made goods. A responsible seller will proudly share the stories of their artisan partners, often including their names, photos, and information about their community.

Before you buy, do not hesitate to ask questions. A transparent and ethical seller will be happy to provide answers.

- “Can you tell me about the artisan or the community that made this bag?”

- “How do you ensure the weavers are compensated fairly for their work?”

- “What is the story or meaning behind the patterns on this specific mochila?”

Caring for Your Woven Treasure

A handwoven mochila is a durable and functional piece of art designed for use. With proper care, it can last a lifetime, carrying stories for years to come. Gentle handling is key to preserving its structure and the vibrancy of its natural dyes.

- Cleaning Instructions: Spot cleaning with a damp cloth is always the first choice. If a full wash is necessary, do so by hand. Use cold water and a very mild, pH-neutral soap. Submerge the bag, gently agitate it, and rinse thoroughly with cold water. Never wring or twist the bag, as this can distort the weave.

- Drying and Storage: To dry, gently press out excess water with a towel. Stuff the bag with clean cloths or paper to help it retain its round shape, and lay it flat or hang it in a shady, well-ventilated area. Direct sunlight can cause the natural dyes to fade. When not in use, store your mochila in a cool, dry place away from moisture.

The Enduring Legacy and Future of the Mochila

Preserving a Millennial Art Form

In an increasingly globalized world, the preservation of ancestral arts like Mochila weaving is a delicate yet vital endeavor. Within the Wayuu, Arhuaco, and other indigenous communities, there is a conscious and concerted effort to ensure these millennial skills are not lost to time. Elders, the revered keepers of this knowledge, are actively mentoring younger generations through community-led workshops and family-based teaching. These initiatives are more than just technical training; they are a transference of cosmology, history, and identity, ensuring that each stitch continues to carry the weight of tradition. The survival of the Mochila depends on this sacred intergenerational dialogue, safeguarding it as a living, breathing part of Colombia’s cultural fabric.

Simultaneously, technology has emerged as an unexpected and powerful ally. Digital platforms and social media have provided a direct conduit from the remote landscapes of La Guajira and the Sierra Nevada to a global audience. Through ethical e-commerce sites and direct-to-consumer models, artisan cooperatives can now share their stories and sell their work without relying solely on intermediaries. This digital connection not only fosters greater economic autonomy but also facilitates a more profound cultural exchange, allowing consumers to understand the deep significance behind their purchase and connect with the weaver who created it.

Innovation Meets Tradition

The future of the Mochila is not static; it is a dynamic interplay between deep-rooted tradition and contemporary creativity. While the core techniques and spiritual foundations remain unchanged, a new generation of artisans is thoughtfully exploring the boundaries of the craft. Some weavers are experimenting with more modern color palettes or developing abstract interpretations of classic Kanasü and Sierra Nevada motifs. Others are innovating with subtle variations in form and function, adapting the timeless bag for modern life while meticulously honoring its authentic spirit. This evolution is not a dilution of the art form but a testament to its vitality and its capacity to adapt and remain relevant. For those interested in experiencing these traditions firsthand, consider visiting areas like Minca or the Palomino region.

Ultimately, the Colombian Mochila stands as a powerful symbol of cultural resilience. It is a narrative woven in thread, a testament to the enduring strength of indigenous communities who have protected their heritage against centuries of change. Far more than a fashion accessory, it is a piece of living history, a holder of thought, and a vibrant expression of an identity that continues to thrive. As it moves forward, the Mochila carries with it the stories of the past and the creative promise of the future, forever a cherished emblem of Colombian artistry.