Understanding Exposure

Unlock the secrets of perfect photos by mastering aperture, shutter speed, and ISO settings.

Ever looked at a perfectly exposed photograph and wondered how it was achieved? Understanding exposure is the fundamental key to unlocking your camera's potential and capturing the images you envision. This article demystifies the concept of exposure, guiding you through its essential components to help you master your camera's settings.

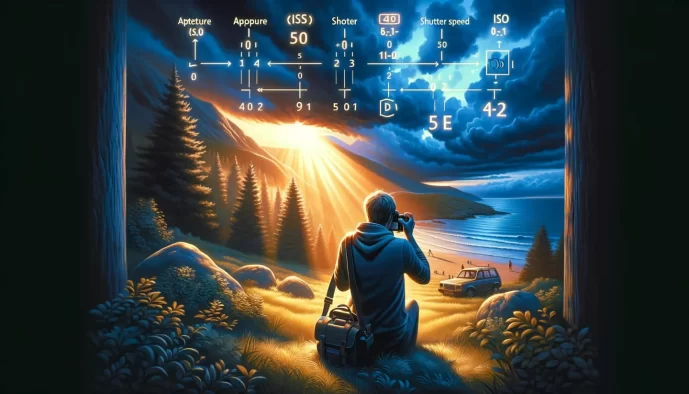

We'll dive deep into the "Exposure Triangle," breaking down its three crucial pillars: Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO. By understanding how these elements work together, you'll gain the confidence to control light and consistently produce beautifully balanced photographs, whether you're a beginner or looking to refine your skills.

Essentials

What is Exposure in Photography?

The Core Concept: Capturing Light

At its most fundamental level, exposure is simply the amount of light that you allow to reach your camera’s digital sensor. Think of photography as a process of “collecting” light to create an image. Exposure is the measurement of how much light you’ve collected. This single concept is the foundation of photography, as it directly determines the overall brightness or darkness of your final photograph. Learning about the exposure triangle will be crucial here.

To put it simply, a photograph that is “correctly exposed” looks natural to the human eye—it has a good balance of shadows, mid-tones, and highlights, without significant loss of detail in the darkest or brightest areas. An underexposed photo is too dark, while an overexposed photo is too bright. Understanding The Exposure Range : What are burned higlights and clipped shadows is key to avoiding these issues.

A helpful way to visualize this is to imagine filling a glass with water. Your goal is a full glass. If you don’t let the tap run long enough, the glass is only partially full—this is like an underexposed photo. If you let it run for too long, the water overflows and makes a mess—this is an overexposed photo, where bright areas are “blown out” to pure white. A perfect exposure is like stopping the tap the moment the water reaches the brim, resulting in a perfectly full glass.

Why Moving Beyond Auto Mode Matters

Your camera’s “Auto” mode is incredibly clever. It analyzes a scene and does its best to produce a correctly exposed image by making all the decisions for you. While this is great for quick snapshots, it has significant limitations. The camera doesn’t know your creative intent; it only knows how to find a safe, middle-of-the-road average. It might see a dramatic sunset and try to brighten the dark shadows, ruining the mood you wanted to capture. Mastering your camera settings is paramount for creative control.

By learning to control exposure yourself, you move from being a passive picture-taker to an active photographer. You gain the power to make deliberate creative choices. Do you want a dark, moody portrait with deep shadows? Or a bright, airy landscape? Do you want to freeze a bird in mid-flight or blur the motion of a waterfall? Understanding and manipulating exposure is the key that unlocks this level of artistic control and allows you to translate the vision in your mind into a finished photograph. This is the essence of Beginner’s Photography 101.

The Exposure Triangle: The Three Pillars of Light

Introducing Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO

If exposure is the goal, how do we control it? The answer lies in three fundamental settings that work together in a delicate partnership known as the Exposure Triangle. These three pillars are Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO. Think of them as the three legs of a stool; if you adjust one, you must adjust at least one of the others to keep the stool level—or in our case, to keep the exposure balanced. A good starting point for understanding these concepts is our Beginner’s Photography 101 guide.

Mastering photography is largely about understanding how these three elements interact. Changing one doesn’t just affect the brightness of your image; it also introduces a unique creative side effect. The magic happens when you learn to balance them not just for a correct exposure, but to achieve a specific artistic vision. Changing your aperture affects the background blur, adjusting shutter speed controls how motion is captured, and tweaking the ISO impacts image clarity. Together, these form the core of camera settings mastery.

This relationship is a constant balancing act. If you want a blurry background (which requires a specific aperture setting), you’ll have to adjust your shutter speed or ISO to compensate and ensure the photo isn’t too bright or too dark. This is all part of achieving proper exposure and avoiding issues like burned highlights and clipped shadows. In the next sections, we’ll break down each of these three pillars one by one to see exactly how they work and what creative power they hold.

Pillar 1: Aperture

What is Aperture?

Think of aperture as the adjustable opening inside your camera lens through which light travels to reach the sensor. It functions much like the pupil of the human eye. In a dark room, your pupil dilates (gets wider) to let in as much light as possible. In bright sunlight, it constricts (gets smaller) to limit the amount of light. Your lens’s aperture does the exact same thing, giving you precise control over how much light contributes to your photograph.

How Aperture is Measured: F-Stops

Aperture size is measured in units called f-stops, which you’ll see written as f/1.8, f/4, f/11, and so on. Here’s the one tricky part you need to remember: the numbering is counter-intuitive. A smaller f-number corresponds to a larger opening, while a larger f-number corresponds to a smaller opening.

- A small f-number (like f/1.8 or f/2.8) means the aperture is wide open. This lets in a lot of light, which is ideal for darker conditions.

- A large f-number (like f/11 or f/16) means the aperture is very narrow. This lets in very little light, making it suitable for bright, sunny days.

The Creative Effect: Depth of Field

Beyond simply controlling light, aperture is one of your most powerful creative tools because it directly controls the Depth of Field (DoF). Depth of field refers to how much of your scene, from front to back, is in sharp focus. By changing your f-stop, you can completely transform the look and feel of your photo. This is a fundamental concept in Beginner’s Photography 101.

- Large Aperture (small f-number, e.g., f/1.8): This creates a shallow depth of field. Only a small sliver of your scene will be sharp, while the foreground and background melt away into a beautiful blur. This is the secret to professional-looking portraits where the subject pops against a soft, non-distracting background.

- Small Aperture (large f-number, e.g., f/11): This creates a deep depth of field. It keeps a much larger portion of the scene in sharp focus, from the flowers at your feet to the mountains in the distance. This technique is perfect for sweeping landscape photography where you want every detail to be crisp and clear.

Pillar 2: Shutter Speed

What is Shutter Speed?

If aperture is the size of the window letting light in, shutter speed is the amount of time that window stays open. It’s the duration for which your camera’s shutter opens to expose the sensor to light. Think of it as a curtain that quickly opens and closes in front of the sensor. The length of time it remains open is your shutter speed, and it has a profound impact on both the brightness of your image and how motion is captured. Understanding this is a key part of camera settings mastery.

How Shutter Speed is Measured

Shutter speed is measured in seconds or, more commonly, fractions of a second. On your camera display, you’ll see values like 1/1000, 1/60, 1/4, or whole numbers like 1″ or 2″ (the ” symbol indicates a full second). The relationship to light is very straightforward:

- A fast shutter speed (e.g., 1/1000s) means the shutter is open for a tiny fraction of a second. This lets in very little light and is ideal for bright, sunny days.

- A slow shutter speed (e.g., 1/30s or 2″) means the shutter stays open for a longer period. This allows much more light to hit the sensor, which is necessary for shooting in darker conditions.

These settings are fundamental to achieving proper exposure and are part of the core concepts in mastering the exposure triangle.

The Creative Effect: Capturing Motion

Beyond controlling light, shutter speed is your primary tool for controlling motion. This is where photography gets truly dynamic. By choosing a specific shutter speed, you decide whether to freeze a moment in time or to embrace its movement.

A fast shutter speed is used to freeze motion. Think of a speeding race car, a bird in flight, or your kids running in the yard. A speed of 1/500s, 1/1000s, or even faster will capture these subjects with crisp, sharp detail, stopping them in their tracks and revealing a moment invisible to the naked eye. This is a key technique in street photography.

Conversely, a slow shutter speed creates motion blur. This is a powerful artistic technique used to convey movement and energy. It can turn the headlights of passing cars into vibrant light trails or transform a cascading waterfall into a smooth, silky curtain of white. When using slow shutter speeds (typically anything slower than 1/60s), it’s crucial to use a tripod. Any tiny movement of your hands will cause the entire image to blur, not just the moving subject. A tripod ensures your camera remains perfectly still, keeping the static elements of your scene (like rocks and trees) sharp while the moving elements (like water) blur beautifully. This is essential when shooting in low light or for long exposures, and is covered in detail in our guide on using a tripod from beginner to expert.

Pillar 3: ISO

What is ISO?

The final pillar of our exposure triangle is ISO. Unlike aperture and shutter speed, which are mechanical adjustments, ISO refers to your camera sensor’s sensitivity to light. It’s an electronic setting that brightens your photo after the light has passed through the aperture and hit the sensor for a set amount of time. Learning about the exposure triangle is fundamental to photography.

For those who remember the days of film photography, this concept is easy to grasp. ISO is the digital equivalent of film speed (or ASA). Back then, you’d buy a roll of film rated at 100 for a sunny day or a roll rated at 800 for shooting indoors. In the digital world, you can change this sensitivity from shot to shot with the press of a button.

How ISO is Measured

ISO is measured on a standard scale, with each number representing a doubling of sensitivity. A typical scale looks like this: 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, and beyond. Moving from ISO 200 to ISO 400, for example, makes your camera twice as sensitive to light, allowing you to get the same exposure with a faster shutter speed or a smaller aperture. Understanding ISO in photos is key to controlling your images.

- Low ISO (e.g., 100, 200): This is your camera’s base sensitivity. At these settings, the sensor is least sensitive to light, which means it requires plenty of light for a proper exposure. The benefit is that it produces the highest quality image with the finest detail and least amount of interference. This is ideal for shooting outdoors on a bright day or in a studio with controlled lighting. For more on this, check out our guide on understanding natural light.

- High ISO (e.g., 1600, 3200): These settings make the sensor much more sensitive to light. This is incredibly useful for shooting in dark environments—like a candlelit dinner, an indoor concert, or a nighttime cityscape—without needing a flash or a tripod. It allows you to use faster shutter speeds to freeze motion even when light is scarce. For specific advice on dark environments, consider our street photography tips.

The Trade-Off: Digital Noise

Increasing the ISO might seem like a magical solution for low-light situations, but it comes with a significant trade-off: digital noise. As you increase the ISO, you are essentially amplifying the light signal captured by the sensor. This amplification process also boosts any imperfections in the signal, which appear in your image as a grainy texture, often described as “noise” or “grain.”

This noise can degrade the overall quality of your photograph, reducing its sharpness, fine detail, and color accuracy. While modern cameras are incredibly good at handling high ISO settings, the fundamental principle remains. For this reason, a good rule of thumb for photographers is to always use the lowest ISO possible for the given lighting conditions to ensure the cleanest, highest-quality image. This ties into achieving proper exposure.

Putting It All Together: The Balancing Act

How the Triangle Works in Practice

Understanding aperture, shutter speed, and ISO individually is the first step. The real magic happens when you see them as an interconnected team. Think of it this way: you can’t change one setting without affecting the others if you want to keep your exposure consistent. They are in a constant dance, and your job is to lead. This concept is central to mastering the exposure triangle.

Let’s walk through a common scenario. Imagine you’re taking a photo of a landscape and your initial settings are an aperture of f/4, a shutter speed of 1/250s, and an ISO of 100. The photo is perfectly exposed, but you notice the mountains in the background are slightly soft. You want more of the scene in sharp focus, so you decide to make your aperture smaller by changing it to f/8. Learning about aperture is key to understanding this.

By moving from f/4 to f/8, you’ve significantly reduced the amount of light entering the lens. If you take the photo now, it will be very dark, or underexposed. To compensate and bring the brightness back to the correct level, you must adjust one of the other two pillars. You could:

- Slow down the shutter speed: To let the same amount of light back in, you could slow your shutter speed from 1/250s to 1/60s. This keeps the shutter open longer, balancing out the smaller aperture. Understanding shutter speed is crucial here.

- Increase the ISO: Alternatively, you could make the sensor more sensitive to light by raising the ISO from 100 to 400. This brightens the image to compensate for the light lost at f/8. ISO in photos plays a vital role in this adjustment.

This is the balancing act in its purest form. A creative choice (increasing depth of field) required a technical adjustment (slower shutter or higher ISO) to maintain a correct exposure. This entire process is part of achieving proper exposure.

Using Your Camera’s Light Meter

So, how do you know when your settings are balanced? You don’t have to guess. Your camera has a powerful tool built right in: the light meter. When you look through your viewfinder or at your camera’s LCD screen in a semi-automatic or manual mode, you’ll see a small scale, usually with a ‘0’ in the middle and numbers like -2, -1, +1, and +2 on either side. This is a fundamental aspect of camera settings mastery.

This meter is your guide to exposure. It constantly measures the light in the scene you’re pointing at and tells you what it thinks the final exposure will be with your current settings. Here’s how to read it:

- Indicator at 0: The camera believes your settings will result in a “correct,” or balanced, exposure. This is your baseline target.

- Indicator in the minus (-) range: The camera is warning you that the image will be underexposed, or too dark. To fix this, you need to let in more light by using a wider aperture (smaller f-number), a slower shutter speed, or a higher ISO.

- Indicator in the plus (+) range: The camera is telling you the image will be overexposed, or too bright, potentially losing detail in the highlights. To fix this, you need to let in less light by using a smaller aperture (larger f-number), a faster shutter speed, or a lower ISO.

As you turn your camera’s dials to adjust your settings, you will see the indicator on the light meter move in real-time. Your goal is to adjust the three pillars of the exposure triangle until that little indicator rests on ‘0’. This simple tool is the key to taking control and achieving the exposure you envision. For those new to photography, exploring Beginner’s Photography 101 can provide a solid foundation.

Mastering Camera Modes for Exposure Control

Understanding the exposure triangle is the key, but your camera offers intelligent shooting modes that act as a bridge between full-auto and full-manual. These “semi-automatic” modes allow you to control one or two creative elements while the camera handles the rest, giving you a perfect blend of convenience and control.

Aperture Priority Mode (A or Av)

In Aperture Priority mode, often marked as A or Av on your camera’s dial, you tell the camera which aperture you want to use. You also set the ISO. Based on these two settings, the camera’s internal light meter automatically calculates and sets the correct shutter speed to achieve a balanced exposure. This mode is a favorite among photographers because it provides direct control over the most powerful creative element: depth of field.

When to use it:

- Portraits: When you want that classic creamy, blurry background to make your subject stand out, you can set a wide aperture (like f/1.8) and let the camera figure out the shutter speed.

- Landscapes: When you need everything from the foreground flowers to the distant mountains in sharp focus, you can set a narrow aperture (like f/11) and trust the camera to set a corresponding shutter speed, even if it means a longer exposure on a tripod.

Shutter Priority Mode (S or Tv)

Shutter Priority, labeled S or Tv (for Time Value), flips the script. In this mode, you dictate the shutter speed and the ISO, and the camera chooses the appropriate aperture to get the exposure right. This mode is all about controlling motion—either freezing it in its tracks or blurring it for artistic effect.

When to use it:

- Sports and Action: To capture a sharp, clear photo of a fast-moving athlete or a bird in flight, you can set a very fast shutter speed (e.g., 1/1000s) to freeze the action without any blur.

- Creative Motion Blur: To transform a waterfall into a silky, smooth cascade or capture the light trails of cars at night, you can set a slow shutter speed (e.g., 1 second or longer) while the camera adjusts the aperture to prevent overexposure.

Manual Mode (M)

Manual mode, or M, is where you take off the training wheels. You are in complete command of all three pillars of the exposure triangle: aperture, shutter speed, and ISO. The camera’s light meter will still provide a guide, telling you if your current settings will result in an overexposed, underexposed, or balanced photo, such as those with burned highlights or clipped shadows, but it will not change anything for you. The final decision rests entirely with you.

This mode grants you the ultimate creative freedom, allowing you to override the camera’s suggestions for artistic purposes, such as intentionally creating a darker, moodier image. However, it requires a solid, practical understanding of how the three elements work together and demands your full attention, especially in changing light conditions. For a comprehensive overview of your camera’s capabilities, explore camera settings mastery.

Practical Scenarios: Setting Your Exposure

Theory is one thing, but putting it into practice is where the real learning happens. Let’s walk through three common photographic situations to see how you can apply your knowledge of the exposure triangle to achieve specific creative goals. These scenarios are excellent starting points for moving out of Auto mode and taking control of your camera.

The Classic Portrait

The goal for a classic portrait is often to make your subject pop by creating a soft, beautifully blurred background. This effect, known as “bokeh,” isolates the person from their surroundings and directs the viewer’s eye right where you want it. This is a perfect job for Aperture Priority mode.

- Goal: Create a shallow depth of field for a blurry background.

- Camera Mode: Aperture Priority (A or Av).

- Settings: Start by setting your aperture to a wide opening. This means choosing a low f-stop number, such as f/1.8, f/2.8, or f/4. The lower you can go, the more blur you will achieve. Keep your ISO at its base level (like 100 or 200) to ensure the image is as clean as possible. Your camera will then automatically calculate the correct shutter speed for a balanced exposure.

The Sweeping Landscape

For a breathtaking landscape photo, your objective is usually the opposite of a portrait. You want everything in the scene, from the flowers at your feet to the distant mountains, to be in sharp, clear focus. This calls for a deep depth of field, which you can control precisely in Aperture Priority mode.

- Goal: Achieve a deep depth of field so the entire scene is in focus.

- Camera Mode: Aperture Priority (A or Av).

- Settings: Select a narrow aperture (a high f-stop number) like f/8, f/11, or even f/16. This small opening ensures a large portion of your image will be sharp. Because a narrow aperture lets in very little light, your camera will need a slower shutter speed to compensate. To avoid blurry photos from camera shake, it is essential to use a tripod. Finally, set your ISO to its lowest native value (e.g., ISO 100) for maximum image quality and detail.

Freezing Fast Action

Whether you’re photographing your kids playing sports, a bird in flight, or a speeding car, the goal is to capture a single, sharp moment in time without any motion blur. This is where controlling your shutter speed is paramount, making Shutter Priority mode the ideal choice.

- Goal: Freeze a moving subject to get a sharp, crisp image.

- Camera Mode: Shutter Priority (S or Tv).

- Settings: Set a fast shutter speed—start with 1/500s and increase it to 1/1000s or faster if your subject is moving very quickly. To get a proper exposure with such a short burst of light, you will likely need to be flexible with your other settings. Your camera will open the aperture as wide as possible to help. You will also probably need to increase your ISO, especially if you aren’t in bright, direct sunlight. Don’t be afraid to use ISO 800, 1600, or higher; a sharp photo with a little noise is almost always better than a blurry, unusable one.

Beyond the Basics: Next Steps in Exposure

Once you’ve mastered the interplay between aperture, shutter speed, and ISO, you’re ready to add a couple of more powerful tools to your photography toolkit. These features offer a finer degree of control and a more accurate way to assess your results, moving you from simply getting a correct exposure to crafting a perfect one. Learn more in Mastering Exposure Triangle.

Understanding Exposure Compensation

Have you ever noticed a button on your camera marked with a +/- symbol? That’s the exposure compensation dial. It’s one of the most useful tools you have when shooting in semi-automatic modes like Aperture Priority or Shutter Priority. Understanding Camera Settings Mastery is key to using this effectively.

Its function is simple yet powerful: it allows you to override the camera’s light meter and intentionally make your photo brighter or darker. Your camera’s meter is calibrated to see the world as a neutral “middle gray.” This works well most of the time, but it can be fooled by scenes with a lot of white (like a snowy landscape) or a lot of black (like a subject in a dark suit). In these cases, the camera might make the snow look dull gray or the suit look washed out. By using exposure compensation, you can tell your camera, “I know what you think, but I want this image to be one stop brighter (+1)” or “two-thirds of a stop darker (-0.7).” It’s your way of providing the final creative input, helping you in achieving proper exposure.

Reading the Histogram

While the image on your camera’s LCD screen gives you a good idea of your shot, it can be misleading. The screen’s brightness setting or the ambient light you’re shooting in can easily deceive your eyes. For a truly accurate assessment of your exposure, photographers turn to the histogram.

The histogram is a graph that displays the tonal range of your photograph, from the darkest shadows on the left to the brightest highlights on the right. It shows you exactly how the pixels in your image are distributed across that range. Learning to read this graph is a game-changer; it tells you at a glance if you’ve lost detail in the shadows (a spike on the far left) or “blown out” your highlights (a spike on the far right) in a way that the screen might not reveal. Mastering the histogram is a key step toward achieving technical excellence in every shot you take, and a crucial part of understanding the exposure range.